Introduction:

I remember watching clothing or makeup ads on T.V. when I was younger and noticing how the models constantly resembled each other from ad to ad; tall, ultra-thin and either had blonde hair or brown hair with pale skin.

I remember questioning my appearance and wondered why girls who looked similar to me were not worthy of starring in these ads and coming to the conclusion at seven years old that who I was simply was the wrong thing to be. I felt shame in my chubby cheeks, in my body composition and my body’s refusal to conform to these standards of beauty no matter how little I ate. Such toxic benchmarks for beauty have been scrutinized by the public in the years since and have even been challenged by consumers.

Inclusivity in the fashion industry has been on the rise in recent years, in part because it is currently “on trend”. Inclusivity has become a buzzword in the fashion industry. The days of strict racial homogeneity of heroine chic models on the catwalk have been scrutinized by the modern audience. However; attempts to promote diversity in the entertainment and fashion industries have historically prioritized eurocentric features, faces, voices and bodies that are palatable to White consumers.

So the questions I keep on coming back to are; is the fashion industry truly inclusive and able to reflect the true demographics in today’s society? And how does tokenism come into play when brands are claiming to portray inclusivity in their campaigns?

1. Hierarchy of Representation

From the perspective of many, including those in the industry, fashion has been neglecting Black, Indigenous and people of colour (BIPOC) for, essentially, its entire existence. The “diversity” we frequently see in the fashion industry still feels incredibly homogenous. There obviously appears to be a hierarchy in the representation of people in fashion. The closer a person’s physical characteristics are to resembling eurocentric facial features, hair texture, and body type the more those types of people are used to portray “diversity” and expect entire ethnic groups to identify with that single image even if most don’t look anything like that. This sends the message that the closer you are to looking white the more beautiful you are. This practice by many brands caters to the White gaze.

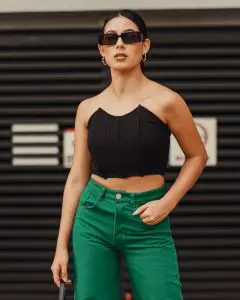

One of the most common instances of this is the constant use of light-skin biracial women and the expectation for all women of colour to identify with this image when that isn’t the case. The tokenization of these biracial models is a blatant attempt to lump a diverse audience into one category. Our society’s foundation for the idea of beauty is based on harmful standards such as the “golden ratio,” which rates physical traits like eye size, nose width, lip fullness, and hair type – and reiterates the ideal proportions of so-called “universal beauty” which never rank non-European features as most beautiful. Brands need to do more than just appear diverse and inclusive at first glance. People deserve to identify themselves with the images portrayed to the public as to what “beautiful” is through all spectrums of the human experience.

Plus-size models have been long ignored by the fashion industry, and up until now are still reluctant to fill runway shows with show-stopping curves. Brands even go as far to claim their reasoning behind their lack of size inclusivity in their collections is due to the cost of the material. Even if a few plus-sized models are cast for a runway show or campaign shoot they will have to adhere to a specific body type, which is an exaggerated hourglass figure. The fashion industry can not be genuinely inclusive until we see plus-size models with different body types and varied body proportions. According to Refinery29, “at spring ’20, out of 7,390 castings, just 86 plus-size models walked the catwalks”.

Some brands have gone to extensive measures by stretching the meaning of “size-inclusive,” to portray their brand to the public as just that. The models that brands use should truthfully reflect their clientele and give the audience the full range of possibilities of how their clothing might fit on different bodies.

This issue goes deeper than skin tone or body size as well, people with different types of disabilities are constantly being overlooked for opportunities for representation. We have seen brands act in response to calls for greater diversity in regards to gender, race, and body shape. Yet it seems there’s still quite a ways to go when it comes to representing people that have physical or mental disabilities. Ableism needs to be addressed especially when speaking on inclusivity and what it should look like. The image of a disabled person having a place in high fashion is virtually non-existent. It is crucial to advocate for an industry that fundamentally cares for and represents those society has labelled as disabled. It’s necessary to perpetuate the message that disabled people do deserve to see themselves be represented and recognize themselves in the fabrics of fashion.

2. Intersectional Identities

People with intersectional identities such as a Latinx plus-size trans woman are yet to be repeatedly represented or even frequently sought after in the industry. Intersectionality does exist, such identities as sexuality, race, gender identity, and body size do not exist in a vacuum. Fortunately, we are starting to see people with such intersectional identities on the catwalk, however; the number is so low it barely scratches the surface.

It is noted that the plus-sized, black and transgender model Jari Jones walked for the Gypsy Sport Spring 2020 runway, and walked a total of two shows in New York. We need more than just one or even two models to “prove” fashion has become inclusive. She was merely used as a symbolic effort of diversity and inclusivity, in other words for “tokenism”. The number of non-binary and transgender models have actually dropped since the year before.

3. The Façade

The Facade – Are the changes we see genuine or just a strategic business move to stay relevant? Much of the changes we’ve seen in the media have simply been cosmetic to boost a company’s image. The majority of “diversity” brands throw at the public is only skin deep, the majority, if not all the people behind the scenes such as hair, makeup, photographers and people making the decisions in the boardrooms are the same type of people that have been occupying those spaces for its entire history, which prevents change from happening deep within.

As Naomi Campbell told a Wall Street Journal conference in 2019: “It [inclusivity] needs to go deeper … We want to see within the actual companies, in the offices, are you going to give diverse staff a seat at the table to advise and be part of the projects that you do? … We need to put diversity behind the desk.” If diversity is not accurately reflected in the roles making the big decisions, then failure and slip-ups are almost always unavoidable. It’s only when true diversity becomes an integral aspect of a brand, that is when the power of inclusive fashion develops into something unstoppable.

Conclusions

The historically harmful systems and standards of beauty that have lingered for far too long and have kept many locked out of the industry for decades, and people are only now beginning to undertake the work to evolve the status quo. it will be a long journey, but one that is worth taking to allow fashion to reflect a more authentic and honest dimension of society.